4. Pitching your story’s emotional hook

"Fishing hooks on white surface" by daniel jaeger is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5.

‘I never take on a client unless I can pitch their book in twelve words.’ UK literary agent

Figuring out the pitch is perhaps the most crucial aspect of selling your book. The pitch is how you connect the book to potential readers. But we have very little time and space to get their attention. Readers are busy and being constantly bombarded by information. So how do we make our pitch cut through the noise and stand out?

Firstly, we should write short. One of the most well-known agents in UK publishing has said he won’t take on a new client unless he can pitch their book in twelve words or fewer. Most people react with horror when I tell them this. It’s impossible! Ridiculous! Nonsense! But, actually, if you can’t say what a book is one sentence can you confidently say you understand it or know it at all?

It was Pascal who said (I summarise), ‘I’d have written a shorter letter if I’d had more time’.

Concision does take time, but it also focuses the attention on what is truly important. What makes your book your book? A former Penguin Books copywriter turned novelist calls this a book’s backbone (see this for more information). Pitching your story in one line forces you to keep only what matters and ditch everything else: is it the stakes, the world, the themes, a character, a journey? Just as importantly, your pitch becomes an anchor: a holdfast that will keep you from drifting too far from this central crucial idea when it comes to writing your blurb. Let’s reach for another metaphor. This should be the kernel around which your story has accreted.

Secondly, to inspire interest in others a pitch requires some tension: it should fizz. The elements in it should resonate in some sense, whether in opposition or harmony or even pleasing discord or offer up something that is just plain unexpected. This is where your word choices and structure become vital.

Thirdly, your pitch requires an emotional hook of some sort. Yes, we are treading into the shimmering waters of advertising terminology. But without engaging the emotions of your reader your book just a block of dead wood. Readers need to feel something, a connection of some sort to your story (an irresistible desire to read it?). The cover and title should have stirred their emotions enough to get them to engage with your book as an object. Thus, sufficiently buttered up, they are ready for your pitch to bring the story alive.

But hang on. The pitch isn’t the blurb (not yet, anyway). It might form part of the blurb, but mostly it is the beating heart of your blurb: the hooky idea that brings it all to life. I’m suggesting we figure out our pitch before we begin writing our blurb (in the same way that we figured out what kind of story we are selling and just who it is we are selling that story to).

Which twelve words or single sentence hookily describes our book? And just as we looked at story types, there are likely to be a few different ways in which we can do it.

Let’s make a start by first of all writing down our story’s backbone. This is the core of your story – why you wrote it or what you discovered in writing it. Screenwriter Craig Mazin says that when reaching for story backbones they should be thematic arguments. For example, the argument/theme of Finding Nemo is – if you love someone, set them free. Is that true? Watch the movie and find out.

Below are some backbones I’ve jotted down for some well-known stories.

1. The least of us is the best of us. (The Lord of the Rings)

2. Love with your heart. Marry with your head. (Pride and Prejudice)

3. An orphan just wants to be loved. (Jane Eyre)

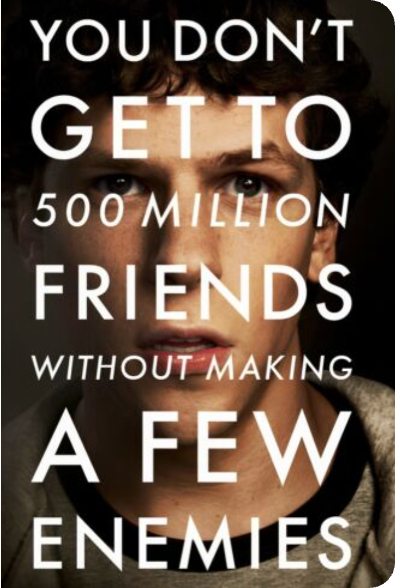

4. You don’t get to the top by being nice. (The Social Network)

5. It’s hard to be human when everyone else is a monster. (I Am Legend)

6. To be human, act human. (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep/Blade Runner)

7. Men and women can’t just be friends. (When Harry Met Sally)

What do these lines tell us? Very little on an initial reading. And they will almost certainly apply to countless other stories as well as the specific ones that inspired these lines. That doesn’t matter. What these lines will hopefully do – and your mileage may vary, this is not a science – is trigger some emotional recognition in you (remember our archetypal story types), depending on your susceptibility to certain kinds of idea.

At the moment, that is all they are – just ideas or arguments. What they don’t yet do is pitch a story. Let’s revisit them, adding some story elements (conveniently, some turn into movie straplines):

1. To destroy vast, corrupting evil turn to the small but good-hearted. (The Lord of the Rings)

2. Must a straitened but eligible young woman choose between love and marriage? (Pride and Prejudice)

3. Can an orphan find love and a home in a loveless world? (Jane Eyre)

4. You don’t get to 500 million friends without making a few enemies. (The Social Network – also, its strapline.)

5. The last man on Earth is not alone. (I Am Legend – also, its strapline.)

6. The man hunting androids starts to fear he’s not human. (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sleep/Blade Runner)

7. Can best friends sleep together and still love each other next morning? (When Harry Met Sally – almost the movie strapline)

We’re hopefully seeing two things here. First, some sense of the stories involved. But more importantly we should have a greater sense of what is at play – the stakes, the themes, the forces of good and evil, the tensions that will be driving each story. They should also, if they are doing their job correctly, provoke a little flutter in our hearts.

For instance, I’m a sucker for stories in which characters face impossible odds (they’ve no chance!) or tales in which the rug is ripped out from under you halfway through (you’re living a lie). As I said earlier, we need to give the lines some frisson and that is why I’ve reached for some with tension in them – small vs big, head vs heart, friends vs enemies, last man vs not alone. Opposites provide tension. Alternatively, you can try juxtaposing something unexpected or counterintuitive.

If you find it hard summarising your story in twelve words, write something longer and then start shaving words off it. Write long to write short, as Pascal didn’t quite express it.

Next – now that we’ve determined our story type, our audience and what our pitch is going to be – we’ll finally get around to starting to write our blurb.

The fourth of eight in a series of posts on how to write a novel’s cover copy, revised and republished from original publication at the Milford SF writers’ blog in Summer 2020.